Here’s an interesting statistic. If you believe the research, at least 50% or more of PMO (project management office) organizations fail within the first 3 or 4 years of inception. There’s a very scholarly article from the Project Management Institute that lays it all out in excruciating detail [LINK] (Spalek 2014) It even includes a fancy 5 circle Venn diagram if you appreciate those sorts of things.

While there’s long lists of contributing factors that various researchers try to glean from surveys, I honestly don’t think they tell it like it is, nor how to truly solve for it.

In my experience, here’s all you need to know. Most PMOs fail because they lack flexibility.

Understanding the Lifecycle of a Project Management Organization

To put the problem into perspective, it helps to understand the lifecycle of a new PMO before it fails. It typically goes like this…

In the beginning there’s a groundswell of excitement. Frustrated by poor results, people go around singing the praises of having project professionals, certifications, the need for best practices, and how much better things could be. A sponsor assigns a respected leader and they start pulling together a group of project management minded folks. If it were the late 1920’s you could imagine people in freshly pressed suits and flapper dresses merrily singing “Happy Days are Here Again.”

To get things going, the PMO leaders will host some workshops to define standards, training classes, tools, and templates. Undoubtedly, everyone faithfully nods their heads in agreement that this is good.

Then the real work starts. People get assigned to lead important projects and team members feel pride in their contributions. Status reports start flying, most of the tools and standards help, and projects start moving forward.

Because most big projects take time to deliver, at least a year passes without much fuss. As that happens, the individual project managers establish close relationships with leaders in the area or function that they serve. Then a strange but predictable phenomenon happens. The PMO project managers go “native” within the specific area of the company they support. They start to identify more with function or area sponsors than they do with the PMO.

Another year passes and the executive team comes back to the PMO asking for help on new important projects. Why? Because that’s what the PMO is supposed to help with.

Excited by the opportunity to contribute, PMO leadership starts looking around to find project managers to meet the need. Much to their surprise, they discover that it’s really hard to reallocate their best project managers to new efforts. That’s because sponsors don’t want to let their good project managers go, and the project managers, who’ve gone native, don’t want to move to a new area.

To avoid angering people, most PMO leaders are really left with two options. One bad and one even worse. They can either recommend hiring more people to meet the increased demand or pull people from existing projects. This might be OK initially, but the second or third time the PMO comes asking for more headcount, or reallocating embedded project managers, executive leadership starts to think twice.

The tipping point

It’s typically at this point where the following logic plays out within

the sponsoring executive teams:

- “Hey, our project management standards are defined. Folks already know the best practices, so why are we paying overhead for somebody to manage these best practices? That seems like low value work if you ask me.”

- “My requests for PMO support are slow and often result in demands for more headcount or pulling talent from another important effort. Why should we work through the hassle of some bureaucratic exercise when I can simply hire project managers on my own?”

- “Wait a minute. Good project managers are already embedded within the various functions. Let’s just cut the central PMO overhead, leave the project managers to report within the function, and be done with it. We’ll save a few bucks and still get the same results. And really, if additional talent is needed, the functional leaders are perfectly capable of hiring people within their team.”

Poof! Very shortly afterwards there’s no more PMO and HR is touting cost savings from their latest RIF (reduction in force) Of course, five years pass, new leaders enter the organization, collective amnesia sets in, and the whole cycle starts all over again. Queue up the band to play “Happy Days are Here Again“…yet once again.

Now I’m not saying this is the same exact story for every PMO, however, I’ve talked with a lot of people, and worked with a lot of different companies, and there are some common themes here. The primary theme being;

PMO failure isn’t a result of improperly applying some project management tool or process. It is a failure of organizational design and stakeholder management.

How to Break the Cycle of PMO Failure

First, it’s important to recognize that this is a unique challenge for project organizations. That’s because most other organizations are relatively operational. Accounting, finance, marketing, operations, etc… typically have regular cadences and workloads that can be forecasted. Whereas, the need for projects is highly variable depending on ever changing conditions both internal and external to the company.

Breaking the cycle requires two key actions:

- Designing a PMO organization for flexibility.

- Setting clear expectations with executive project sponsors and project managers.

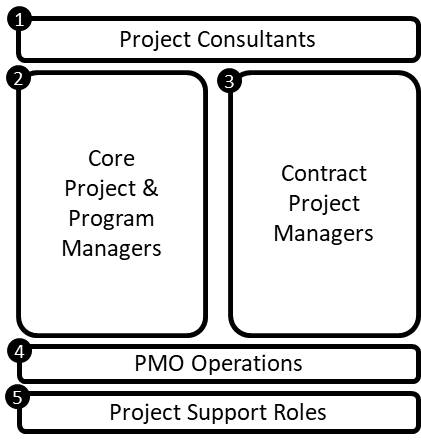

While there isn’t a one size fits all approach to organizational design, the visual below outlines a handful of core components that contribute to creating a flexible PMO organization. An explanation of each element, and how they work together, is as follows.

(1) Project Consultants

Consider maintaining a small group of highly experienced project professionals. These should be some of your most senior people. What really distinguishes these PMO team members is their ability to engage with executives, adapt, analyze, and perform in practically any project related scenario. Similar to special forces in the military, they are not intended to be used for long-term engagements. They get in, assess, accelerate, organize, and engage the right resources. Then they leave.

Deployment of these team members typically comes with an understanding that they will only be engaged for 30, 60, or 90 days. This ensures that there is always highly skilled capacity becoming available to address new needs as they emerge. Thus, the PMO never has to offer a hard “NO” when resources are requested. And trust me, there are always new needs.

Additionally, because these team members are the most senior people in the project organization, they may have formal or informal direct reports from the core project and program managers (#2). This enables them to provide practical, experience based coaching, to develop other team members.

(2) Core Project & Program Managers

This is the bulk of full time project professionals within the PMO. Depending on skill level and experience, these individuals may be assigned to manage individual projects or highly complex programs. However, what differentiates this group from consultants (1) or contract project managers (3) is that they are typically aligned to high value projects that may be active for a prolonged period of time (i.e. greater than 3 months). As such, this part of the organization tends to be one of the least flexible, which is fine, since many large efforts require stability and continuity.

(3) Contract Project Managers

Every PMO should establish formal relationships with multiple external contract project management agencies. This ensures that the organization always has the ability to quickly scale up or scale down the project management workforce. These resources are best deployed on:

- Lower value, lower complexity projects.

- On larger projects that are already well organized and simply need to be maintained until completion.

- Administrative support related needs, under the direction of an experienced internal project leader.

By centralizing a few key agency relationships, PMO Operations (4) is also able to ensure that the contracted organizations are trained and held accountable to the specific standards of the PMO. Centralizing also helps to ensure costs are monitored and controlled.

As an added bonus, depending on how the agency relationships are structured, contract project managers who demonstrate high levels of proficiency may become candidates for full time employment. This minimizes some of the risk and guess work associated with acquiring full-time talent in the open market.

(4) PMO Operations

The operations team is a relatively small, but incredibly important, part of the organization. Just like the conductor of a symphony, they keep everything working together in harmony. They manage things like demand intake, capacity planning, portfolio planning, project reporting, project auditing, training, professional development, definition of standards, management of tools or technology platforms , contract agency oversight, KPI’s, etc…

By keeping work processes running smoothly, this team ensures that flexibility is maintained and resources are continuously optimized.

(5) Project Support Roles

Depending on the industry, size, or maturity of the organization, the PMO may also integrate project support roles. These are specialized skill sets that are often needed during various stages of the project lifecycle to ensure successful outcomes. Examples include:

- Change Managers – Provide training, communications, and adoption support.

- Business Analysts – Defines scope, requirements, and business needs to support project initiation.

- Project Coordinators – Delivers technical and administrative support to project managers.

- Relationship or Client Managers – Works with executive sponsors to cultivate and ensure success of a sub-set of projects within the overall portfolio.

- Financial Analysts – Oversees funding allocations, budget performance, and validation of financial benefits.

This Supports a Project Management Career Model

The other important aspect of maintaining these components within the PMO is that it establishes a framework for professional development and career progression. There’s a natural means for people to enter the organization and progress with increasing opportunities for responsibility and growth. People have a “home” where their skills are appreciated and nurtured. When individuals recognize that they have a clear development path they are less likely to go “native” within individual functions.

This means there will be less turn-over and more people who want to join and stay within the PMO throughout their career. As their individual project expertise grows, so to does the value potential of the organization.

PMO Organizational Design is Only One Part of the Equation

While organizational design helps address the flexibility part of the equation, it’s equally important for PMO leadership to set proper expectations. To accomplish this I recommend that project management organizations establish a simple “engagement plan” directly with the sponsor for every project it supports. It should be less than one-page and include basic items like:

- Resource type, core deliverables, and/or day-to-day responsibilities.

- Expected time commitment.

- Conditions by which the engagement will be ended or re-assessed.

- Clarity that while an individual person may be assigned to their project, they may be re-assigned at the PMO’s discretion and replaced with a resource of similar skill / experience.

- How cost recovery, if applicable, will be managed.

By formalizing the engagement, the PMO communicates three very important messages:

- The function is temporarily obtaining a skilled resource to fulfill an important need and not necessarily a specific individual.

- The tasks, time, and/or conditions necessary for the engagement to be complete. i.e. the exit plan.

- For the individual project professional, it also reinforces that they are performing a service on behalf of the PMO organization. They are part of the PMO team and not the function receiving support.

These three messages establish the “ground rules” necessary to maintain the flexibility of the project organization to support the needs of the broader company or entity.

How You’ll Know It’s Working

At the end of the day, the best PMO design is simply one that works. That means that it’s thriving and not failing. Regardless of what design aspects you consider, maintaining a handful of metrics can guide you in the right direction as the needs of broader organization evolves. Here’s some measures that you might consider to help assess if you’re on the right track.

- Time to staff new PMO requests

- Number new requests open for greater than 2 weeks

- Sponsor satisfaction with PMO engagements. ex. 5 point attribute agreement scale

- PMO team member satisfaction. ex. 5-point attribute agreement scale

- Percentage of PMO engagement across the most important projects/initiatives. i.e. the PMO’s relative market share of initiatives

- Staff retention and/or turn-over

- Audit results of standards from both contract and internal resources.

- Average hourly contractor rates vs. industry benchmarks

And, of course, the most important metric. Whether or not your PMO exists so that it can continue to add value to the organization.

Citations

Spalek, S. (2014). Do you really want your PMO to survive? Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2014—EMEA, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.